Noemi Savková

This text was written at the Faculty of Music of the Janáček Academy of Music and Performing Arts in Brno as part of the project Exploring the Possibilities of the Viola d’Amore through the Creation of a New Composition, supported by funds for specific university research provided by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports for the year 2025.

Introduction

The viola d’amore is classified as a historical instrument, yet (surprisingly) there is a whole range of contemporary compositions written for it. Thanks to its construction and the historical tradition of flexibility in string tuning, the instrument offers composers several possibilities. This text asks how contemporary composers approach the possibilities of the viola d’amore. The use of the viola d’amore in contemporary music after 1970 is explored through analytical studies of four compositions. These compositions were selected from many available compositions to represent a wide range of uses of the various possibilities of this historical instrument.

The use of early instruments in contemporary music is generally an area that has been little researched. In Czech scholarly literature, the viola d’amore is the subject of David Šlechta’s dissertation, Zapomenutý svět violy d’amore (The Forgotten World of the Viola d’amore). The author focusses primarily on the use of the viola d’amore in the works of Leoš Janáček and Paul Hindemith. 1 The following publications are important for understanding the instrument, its possibilities, and historical context. The Viola d’amore, Its History and Development by Rachael Durkin, 2 dissertation Playing with resonance by Daniela Braun, 3 two contributions from the conference Colloque sur les instruments à cordes sympathiques, which were published in the book Amour et sympathie, 4 and Viola d‚amore Bibliographie by Michael and Dorothea Jappe. 5

The following compositions were selected for a deeper exploration of the possibilities of the viola d’amore and its use: Odysseus in Ogygia for six violas d’amore by Rachel Stott, 6 To let go of the universe for viola d’amore and electronics by Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg, 7 Utter/Enunciate for viola d’amore by Þráinn Hjalmarsson 8 a Spikes for viola d’amore, freeze pedal and electronics by Zeno Baldi. 9 For the first composition mentioned, the author discusses it in the text Exploration of the soundworld of the Viola d’amore. 10 These compositions will be examined with a focus on using the potential of the viola d’amore in the area of extended techniques and string tuning.

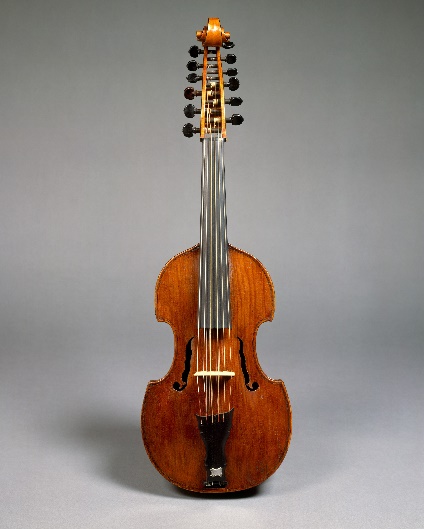

Before discussing the analytical probes themselves, it is necessary to discuss the instrument and its possibilities in general. The viola d’amore is a string instrument that does not have a standardised form. The body of the instrument is based on the soprano viola da gamba. The development of the viola d’amore is extremely rich – from a five-string instrument without sympathetic strings to today’s most common form of the instrument with seven playing strings and seven sympathetic strings. 11 The function of sympathetic strings is primarily to influence tone colour and resonance. Sympathetic strings respond to the vibrations of the playing strings, with the strongest response coming from tones that are related to the lower tones of the harmonic spectrum of tones tuned on the sympathetic strings. 12

Figure 1: GAGLIANO, Joseph. Viola d’amore. Online. In: The Met. C2000-2025. Available from: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/503196. [cit. 2025-12-01].

An interesting fact is that more than sixty contemporary chamber compositions for the viola d’amore were written after 1970, which is a relatively high number compared to other historical instruments. The fact that there are so many compositions for the viola d’amore has a pragmatic explanation. The reason is the demand for these compositions from some viola d’amore players. Perhaps the most prominent role in this is played by Italian performer Marco Fusi, who is proficient in playing the violin, viola, and viola d’amore. Thanks to him, many new compositions for the viola d’amore have been created as he commissions these compositions himself. Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg, a viola and viola d’amore player, composer, and luthier, has also encouraged the creation of several contemporary compositions for the viola d’amore, including her own. Other names worth mentioning here are violist and viola d’amore player Garth Knox, to whom several compositions for the viola d’amore have been dedicated and who has also written several himself, and viola d’amore player and composer Rachel Stott, who has written several compositions featuring the viola d’amore.

Rachel Stott: Odysseus in Ogygia

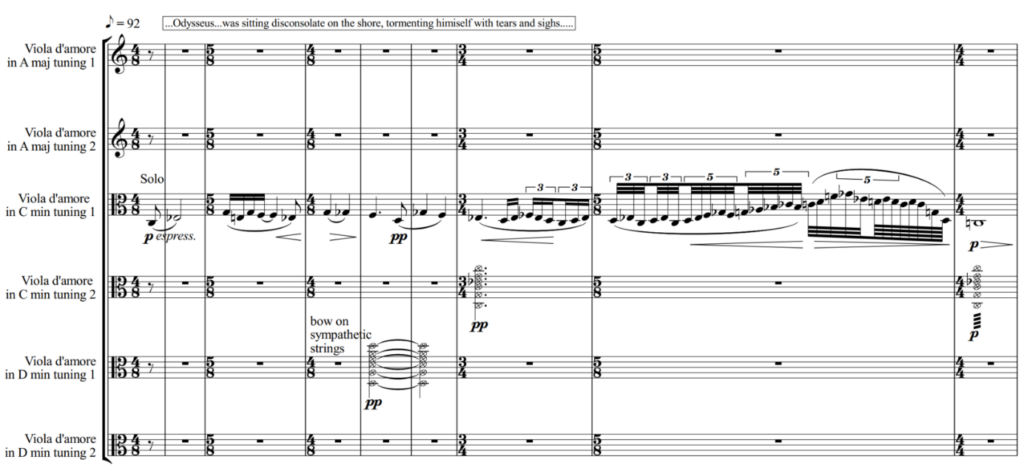

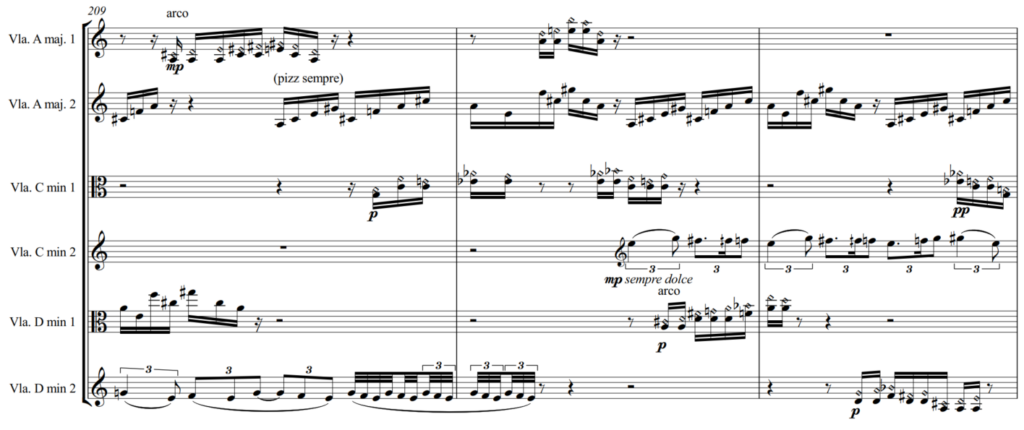

The composition Odysseus in Ogygia, 16 by the British composer and performer Rachel Stott, dates from 2011 and lasts approximately fifteen minutes. Its unusual instrumentation features six violas d’amore, two tuned to A major, two to C minor, and two to D minor. The fact that the composer used three different string tunings provides her with many compositional possibilities, which will be mentioned later.

Stott was inspired to write this piece by the story of Odysseus, who was imprisoned for seven years on the mythical island of Ogygia by the goddess Calypso, who wanted to marry him in exchange for immortality. However, Odysseus longed to return home, and at the command of the god Hermes, Calypso had to release him. The quotes of the story appear in various places in the composition, as can be seen in the first image, and the mood of these quotes influences the musical ideas.

The architecture of the composition is based on several contrasting elements that intertwine in places and mostly recur throughout the piece. In this composition, Stott makes use of many of the possibilities offered by the viola d’amore.

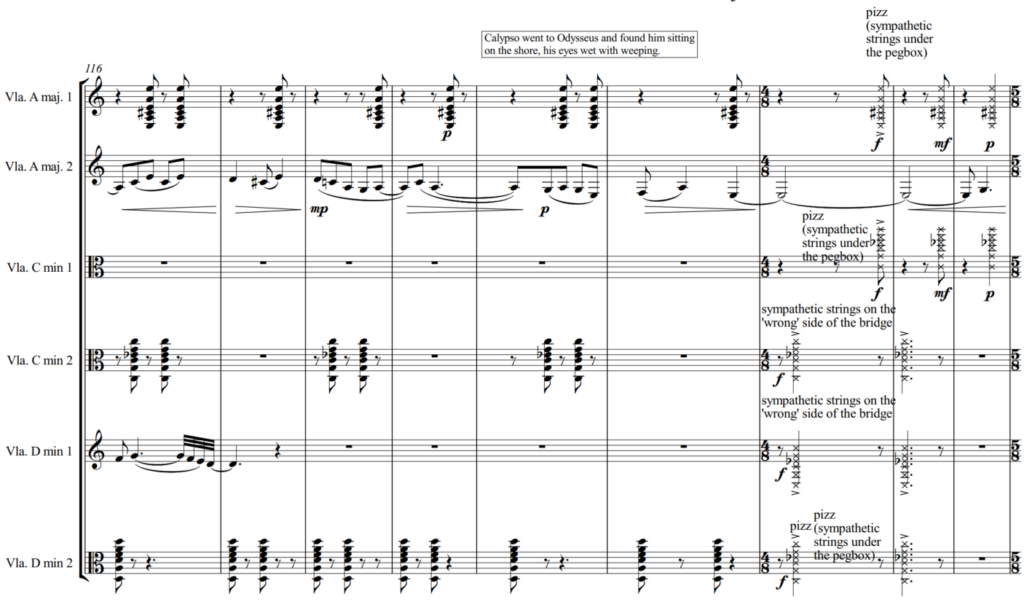

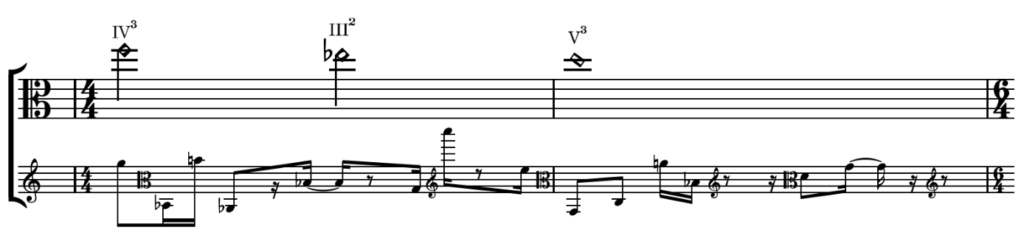

The composition begins with a distinctive melody that appears several times in various forms throughout the piece, sometimes using quarter tones. This melody is coloured by a special extended technique possible only on the viola d’amore, namely playing the sympathetic strings with a bow, sometimes with tremolo. The score shows that the sympathetic strings are tuned to match the strings being played, so that in their longest part (the same as that normally played with a bow on the bowed strings) they sound the chords A major, C minor, and D minor. In other places, there is also a requirement to play the sympathetic strings behind the bridge. This is followed by a fast pizzicato movement, which will form a layer with other structures that will subsequently become independent.

Figure 2: STOTT, Rachel. Odysseus in Ogygia: for six violas d’amore [score]. Rachel Stott, 2011, b. 1–9. Used with the kind permission of the author.

Figure 3: STOTT, Rachel. Odysseus in Ogygia: for six violas d’amore [score]. Rachel Stott, 2011, b. 47–48. Used with the kind permission of the author.

Figure 4: STOTT, Rachel. Odysseus in Ogygia: for six violas d’amore [score]. Rachel Stott, 2011, b. 116–124. Used with the kind permission of the author.

Figure 5: STOTT, Rachel. Odysseus in Ogygia: for six violas d’amore [score]. Rachel Stott, 2011, b. 209–211. Used with the kind permission of the author.

Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg: To let go of the universe

The composition To let go of the universe 17 by the German composer, performer, and luthier Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg is written for viola d’amore and electronic track. The duration of the piece is approximately eleven and a half minutes. The composition dates from 2022.

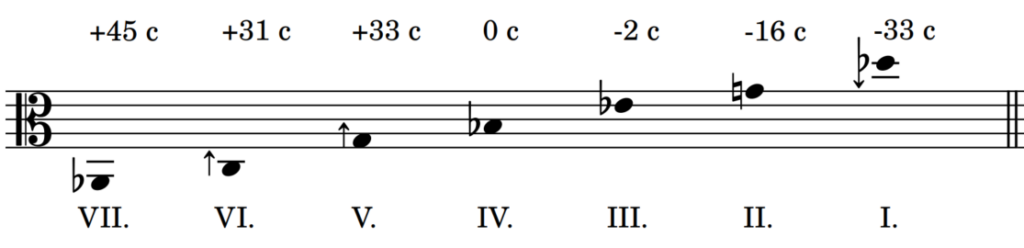

The starting point for this composition, as the author states in the legend of the composition, was the fact that sympathetic strings are essential for the characteristic sound of the viola d’amore, but the possibilities for playing them directly are very limited because they are difficult to access under the playing strings and fingerboard. The electronic track in this composition is based exclusively on the sounds of sympathetic strings played with a bow or pizzicato.

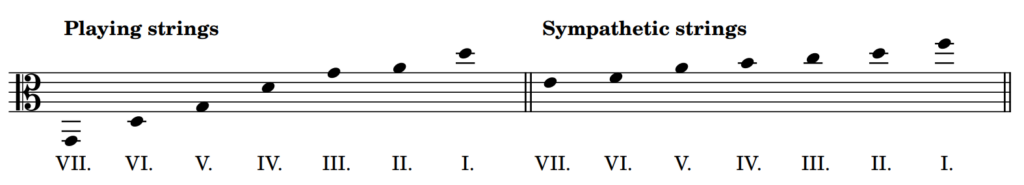

Figure 6: MAYER-LINDENBERG, Annegret. To let go of the universe: für Viola d’amore und Zuspiel [score]. Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg, 2022, tuning of the strings. Used with the kind permission of the author.

The composition begins with pizzicato tones using open strings or harmonics. There is also a thumb strike on the upper edge of the bridge that causes the sympathetic strings to sound. 18 This is notated with a cross-shaped head. Later, long chords on the sympathetic strings are added to the electronic track.

Figure 7: MAYER-LINDENBERG, Annegret. To let go of the universe: für Viola d’amore und Zuspiel [score]. Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg, 2022. Used with the kind permission of the author.

Figure 8: MAYER-LINDENBERG, Annegret. To let go of the universe: für Viola d’amore und Zuspiel [score]. Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg, 2022. Used with the kind permission of the author.

Figure 9: MAYER-LINDENBERG, Annegret. To let go of the universe: für Viola d’amore und Zuspiel [score]. Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg, 2022. Used with the kind permission of the author.

Þhrainn Hjalmarsson: Utter/Enunciate

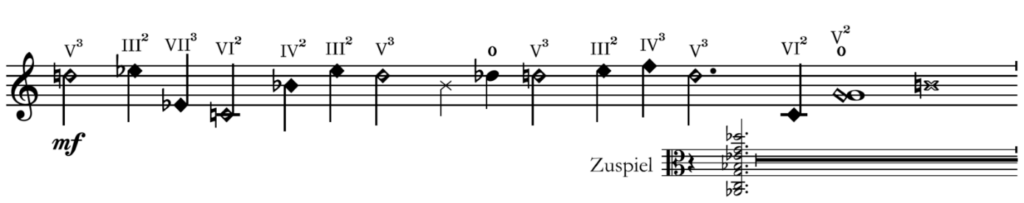

Utter/Enunciate 19 by the Icelandic composer is a composition for viola d’amore lasting approximately eleven minutes. The composer wrote the piece for Marco Fusi. Hjalmarsson prefers a Baroque bow for this composition; according to Daniela Braun, it enhances the tones from the harmonic spectrum. 20 The composer specifies the tuning of both the playing strings and the sympathetic strings, which are not tuned identically.

Figure 10: HJALMARSSON, Þráinn. Utter/Enunciate: for solo viola d’amore [score]. Þráinn Hjalmarsson, 2018, tuning of the strings. Used with the kind permission of the author.

The composer describes the sound concept in detail in the legend of the composition. All notes should be played without a pronounced attack, and all notes should be slowly amplified. Expressive vibrato of the left hand should not be used; the tones should sound as if they were played on open strings. The bow should leave the string in motion, and the strings should be allowed to decay. Silence plays an important role in the composition, and the space for the tones to decay is created by the frequent use of pauses. In general, the performer should play with light bow pressure and with noise in the tone. Each tone should be formed like a syllable in a word, with the help of subtle changes in the pressure of the bow.

There are three tone colours in the composition. There is only one note in the composition where all surrounding strings should be muted. (Marked with a coda symbol.) The brackets above the note mean that the note should be played as an echo or shadow of the surrounding notes, which should be achieved by limiting the volume or using lighter bow pressure. A note in a circle means that it differs from the standard tuning. This deviation ranges from ½ Hertz, which is half a beat per second, to 3 Hz, which is 3 beats per second.

Figure 11: HJALMARSSON, Þráinn. Utter/Enunciate: for solo viola d’amore [score]. Þráinn Hjalmarsson, 2018. Used with the kind permission of the author.

The dynamics in the composition range from pianissimo to mezzo forte and are not related to volume but indicate the pressure of the bow and subtle differences in expression. In this concept, the dynamic markings mean the following: pp = very light pressure, p = light pressure, mf = normal pressure. The overall volume should remain the same throughout and be about the same as when a person speaks with a soft voice.

Zeno Baldi: Spikes

The composition Spikes 21 by Italian composer Zeno Baldi is for amplified viola d’amore, freeze pedal, and electronic track. The composition was also written for Marco Fusi. The length of the piece is approximately eight and a half minutes, and it was composed in 2014.

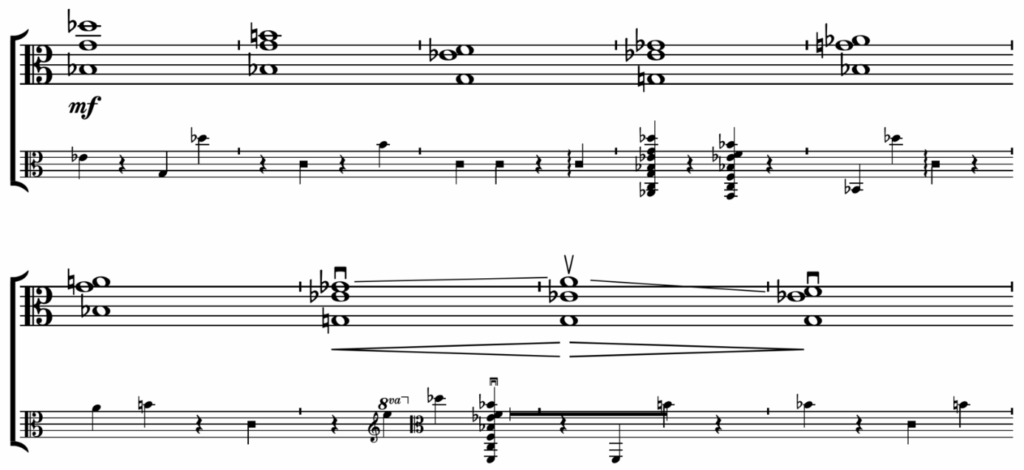

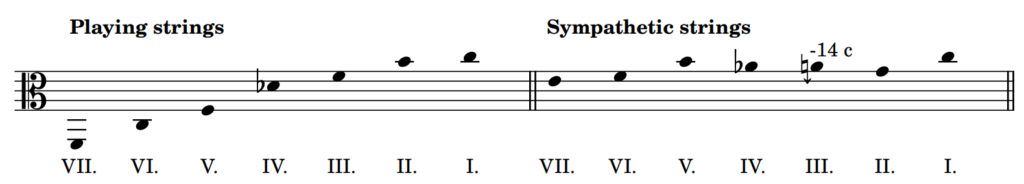

In the composition legend, the author specifies the required tuning of both the playing strings and the sympathetic strings, whereby the sympathetic strings are not tuned identically to the playing strings. A special feature of the tuning of the sympathetic strings is the third string in the standard twelve-tone equal temperament, which is the fifth harmonic tone of the seventh playing string.

Figure 12: BALDI, Zeno. Spikes: per viola d’amore amplificata, freeze pedal e traccia audio [score]. © Casa Ricordi srl, Milano – all rights reserved, 2016, tuning of the strings. Used with kind permission of the publisher.

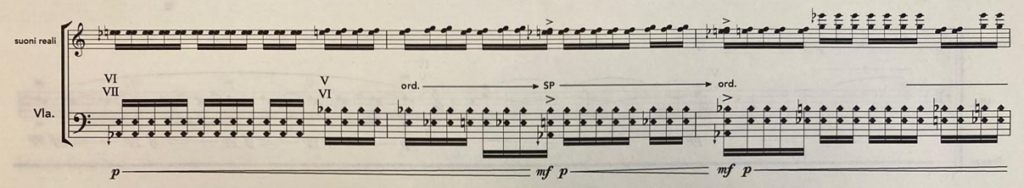

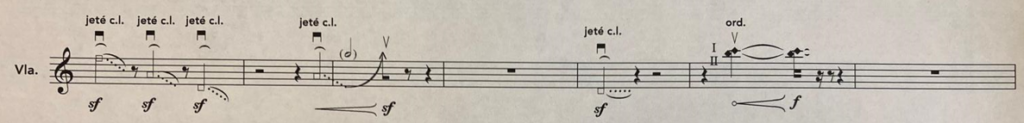

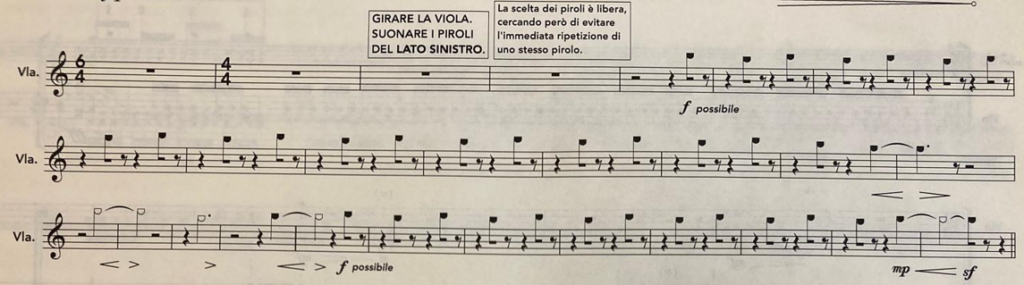

The viola d’amore is used in a very unconventional way with frequently occurring extended techniques. The composition begins with pizzicato playing, however, in unusual places, which the author describes as „pizzicare le corde sul retro dello strumento“, meaning that pizzicato should be played at the back of the instrument, either at the bottom or at the top. This is followed by a dense structure based on longitudinal bowing. This is followed by longer tones of natural harmonics in double stops. Due to the greater number of strings, there are more possible tones played as harmonics than on a modern viola, which was also widely used in the historical repertoire, as evidenced by notes in the publication Viola d’amore Bibliographie by Michael and Dorothea Jappe. 22

Figure 13: BALDI, Zeno. Spikes: per viola d’amore amplificata, freeze pedal e traccia audio [score]. © Casa Ricordi srl, Milano – all rights reserved, 2016. Used with kind permission of the publisher.

Figure 14: BALDI, Zeno. Spikes: per viola d’amore amplificata, freeze pedal e traccia audio [score]. © Casa Ricordi srl, Milano – all rights reserved, 2016. Used with kind permission of the publisher.

Figure 15: BALDI, Zeno. Spikes: per viola d’amore amplificata, freeze pedal e traccia audio [score]. © Casa Ricordi srl, Milano – all rights reserved, 2016. Used with kind permission of the publisher.

Conclusion

An examination of four selected compositions for the viola d’amore revealed the breadth of possibilities offered by this instrument as seen by contemporary composers. The compositions featured commonly used extended techniques for string instruments, such as glissando, multiphonics, overpressure, and col legno playing. Techniques that are more advantageous on the viola d’amore than on the modern viola due to the higher number of strings included bisbigliando and playing with the bow on the pegs.

Contemporary composers have followed in the footsteps of historical composers in their diverse requirements for the tuning of played strings. Rachel Stott’s composition Odysseus in Ogygia for six violas d’amore features three tunings in different keys, which offers interesting possibilities in terms of resonance (e.g., when playing pizzicato on open strings) or arpeggio playing. Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg used a tuning based on natural tuning in her composition To let go of the universe. In the compositions Utter/Enunciate by Þhrainn Hjalmarsson and Spikes by Zeno Baldi, the composers required their own specific tuning for both the playing strings and the sympathetic strings.

The resonance of the instrument was treated in a special way in the composition Utter/Enunciate, in which the composer allowed space for the tones to fade away. Contemporary composers used sympathetic strings in a way that was not used in early music, namely by playing them with a bow or pizzicato in various places. Thanks to the electronic recording, the composition To let go of the universe used many sympathetic string tones that would not have been possible in a live performance.

Summary

The paper “Viola d‚amore in the Works of Contemporary Composers: Analytical Probes into Four Selected Compositions” focuses on examining the use of the viola d’amore in compositions by contemporary authors. It first introduces the instrument in general, with particular emphasis on its characteristic features, especially the flexibility of string tuning, which typically involves up to seven playing strings and seven sympathetic strings, as well as on the function of the sympathetic strings.

More than sixty compositions for the viola d’amore have been written since 1970, four of which were selected for more detailed analysis. In Rachel Stott’s composition “Odysseus in Ogygia” for six violas d’amore, the use of three different tunings was identified. The work also employs unconventional playing techniques involving the sympathetic strings, both with the bow and in pizzicato. The composition “To Let Go of the Universe” for viola d’amore and electronic track by Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg works with the sound of the sympathetic strings within the electronic part, thus achieving sonic possibilities that are otherwise unattainable. The tuning of the playing strings in this piece makes use of natural tuning. Þráinn Hjalmarsson’s composition “Utter/Enunciate” requires a specific tuning of both the playing and the sympathetic strings. The composer works here with bisbigliando and with the resonance of the sympathetic strings. In the composition “Spikes” by Zeno Baldi, the author combines a live instrumental part with an electronic track. He makes extensive use of harmonics as well as extended techniques, such as pizzicato on the sympathetic strings or bowing on the tuning pegs.

Shrnutí

Text Viola d’amore ve skladbách současných autorů: Analytické sondy do čtyř vybraných kompozic se zaměřil na zkoumání využití violy d’amore v kompozicích současných autorů. Nejprve představil nástroj obecně s důrazem na jeho charakteristické rysy v oblasti flexibility v ladění strun, kterých bývá až sedm hraných a sedm sympatetických, a dále pak ve funkci sympatetických strun.

Pro violu d’amore bylo po roce 1970 vytvořeno přes šedesát skladeb, z nichž čtyři byly vybrány k hlubšímu zkoumání. Ve skladbě Rachel Stott Odysseus in Ogygia pro šest viol d’amore bylo zjištěno využití tří různých ladění strun. Byla zde také nalezena netradiční technika hry na sympatetické struny smyčcem i pizzicato. Skladba To let go of the universe pro violu d’amore a elektronickou stopu Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg pracuje se zvukem sympatetických strun v elektronické stopě, čímž dociluje možností sympatetických strun jinak nedostupných. Ladění hraných strun v této skladbě využívá přirozeného ladění. Kompozice Thrainna Hjalmarssona Utter/Enunciate vyžaduje vlastní ladění hraných i sympatetických strun. Autor zde pracuje s bisbigliandem a dozníváním sympatetických strun. V kompozici Spikes Zena Baldiho autor propojuje živě hraný part s elektronickou stopou. Hojně využívá flažolety a také rozšířené techniky, jako je hra pizzicato na sympatetické struny nebo hra smyčcem na kolíky.

Keywords

Viola d’amore, contemporary music, instrument possibilities, tuning, sympathetic strings

References

Literature:

BRAUN, Daniela. Playing with Resonance. Dissertation. Graz: University of Performing and Arts, 2024.

DURKIN, Rachael. The Viola d’amore, Its History and Development. Routledge, 2022. ISBN 9780367513733.

JAPPE, Michael a JAPPE, Dorothea. Viola d’amore Bibliographie. Amadeus Verlag, 1997. ISBN 3-905049-74-0.

Scores:

BALDI, Zeno. Spikes: per viola d’amore amplificata, freeze pedal e traccia audio [score]. Casa Ricordi, 2016. ISMN 979-0-041-41498-0.

HJALMARSSON, Þráinn. Utter/Enunciate: for solo viola d’amore [score]. Þráinn Hjalmarsson, 2018.

MAYER-LINDENBERG, Annegret. To Let Go of the Universe: für Viola d’amore und Zuspiel [score]. Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg, 2022.

STOTT, Rachel. Odysseus in Ogygia: for six viols d’amore [score]. Rachel Stott, 2011.

Interview:

Interview and experimental investigation with Annegret Mayer-Lindenberg, in Köln, 3. 6. 2025.

Strany 1-11/2025